Note to HIC, by Ana Sugranyes, Wisdom Keeper of the Coalition.

On February 2nd, several simultaneous fires devastated forest and housing areas in the Valparaiso Region, Chile: they killed 132 people and burned 7,000 homes over a total of 8,000 hectares in the communes of Viña del Mar, Quilpué and Villa Alemana.

The victims are families from different socio-economic groups; half of them lived in popular settlements, the “campamentos”, as they are called in Chile.

The fire destroyed everything; its causes are various, including the effects of climate change, the absence of risk prevention measures, territorial (mis)planning and, most likely, an intention to destroy.

This kind of disaster is reminiscent of the ‘epidemic’ of fires in the favelas of Sao Paulo, some 10 years ago, which the film “Limpam com fogo” explains so well.

The emergency aid comes from the state and a large voluntary mobilisation, with the removal of rubble, the compilation of a land registry of victims, a bonus of about a thousand dollars per family and all kinds of support around the common pots and pans.

The diagnosis of the drama has been established, with high-tech geo-referenced systems. The state is beginning to define the rules for reconstruction in the tradition of Chilean housing policy: individual subsidies, prioritising the response to affected families with title deeds.

As has already happened after other fires in this coastal region of central Chile – with its rugged topography – the tendency is towards immediate reconstruction, with more or less definitive materials. By obtaining family aid or commercial loans, houses are rebuilt in the same places, sometimes on the same ‘radier’, without even checking the cavities that the fire may have created under the cemented base of these constructions on not very dense plots of land.

The tendency, amidst haste, distrust and individualism, is to repeat the same old serious mistakes of the same old urbanisation, pirate, then regulated by the State, so that new disasters can be repeated.

There are exceptions! We see this with the Movimiento de Pobladores Organizadas, MPO, with its self-managed approach. Amidst adverse housing and institutional conditions, some communities manage to mobilise the strength of organisation to survive the trauma of ‘having lost everything’ and to think about reconstruction from the point of view of risk prevention, regeneration of shelter spaces, firebreaks, higher densities and urban integration.

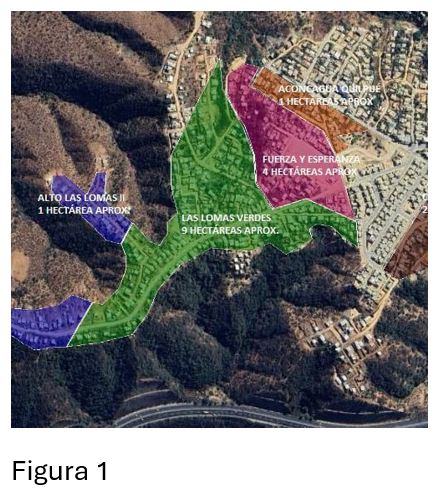

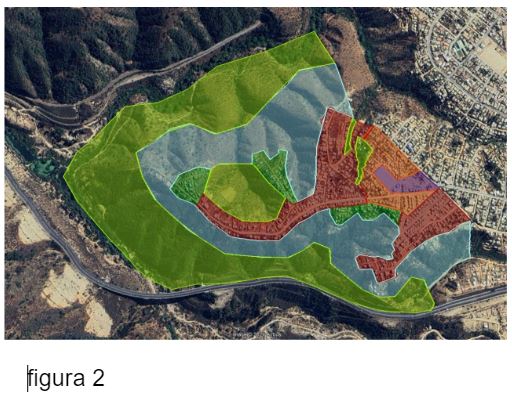

Nine camp committees in the Pompeya Sur sector of the Quilpué district – some 450 families – show the capacity to develop a planned resettlement between organisations and families, thinking about the future despite the precariousness of the moment, analysing safer options, more adequate to the aggressiveness of the environment, and weighing the best possible alternative among various forms of access to housing, in individual or collective property, in greater or lesser density, in cooperatives, leases, or commodatum.

Villa La Unión is in the process of reconsolidation. After more than 5 years of tradition of social and local organisation, legal disputes, fights and some technical pre-feasibility certificates for urbanisation, these communities in occupation are accompanied by a multidisciplinary team, which is gradually being structured between voluntary, professional, academic, student and partisan bodies; an apprenticeship of collective and orderly work, at the service of the local leaders.

Figures 1 and 2 show, on the left, the atomisation of the camps before the fire. On the right, a first attempt at an objective, more compact image appears, designed around a square or citizens’ centre and care, seeking urban integration, and with a firebreak strip, regeneration of a water balance, park areas, vegetable gardens and playgrounds.

Villa La Unión is a great challenge. It is the dream of vulnerable and vulnerable families, just coming out of a traumatic shock, who are thinking about the quality of life of the new generations, and who are facing the adversity of the institutional environment. The struggle will be long and hard, towards municipal recognition of a change in the regulatory plan; before the ministry of social development for emergency aid, before the ministry of housing and urbanism towards a master plan and facilities for different access to housing.

Yes, there is the pain of the disaster, the helplessness of the devastated and criminalised families; there is also the accompanied self-management for the neighbourhood, for the good living of everyone!