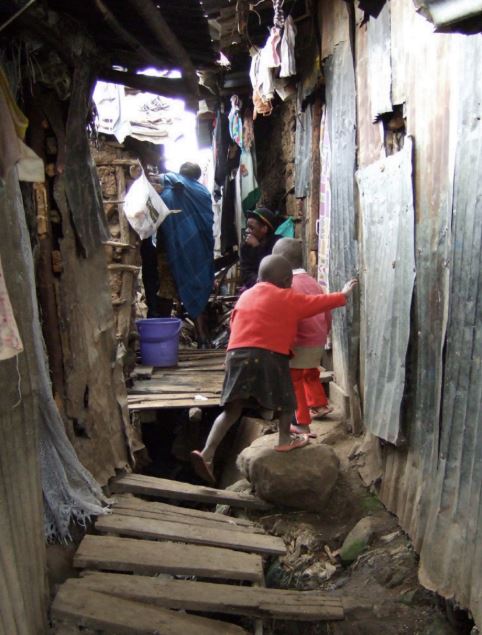

In recent global discussions, informal settlements (tagged systematically as slums) have been identified, analysed and delimited. Plenty of data has been produced about the number of slums, their extension and the number of households and people living there. By default, these informal settlements are considered an illegal phenomenon and linked to other terms like “squatting,” which normally, carries the notion of “criminality.” Instead, the focus should be in identifying the genesis of slums and the factors that force people to live –and in some cases survive- in such harsh conditions. The effects of the government’s disengagement which has been gradually reducing the provision of affordable and social housing, has been severely exacerbated by the privatization of public services and the financialization of land and housing. Who is to blame here for the proliferation of slums?

In recent global discussions, informal settlements (tagged systematically as slums) have been identified, analysed and delimited. Plenty of data has been produced about the number of slums, their extension and the number of households and people living there. By default, these informal settlements are considered an illegal phenomenon and linked to other terms like “squatting,” which normally, carries the notion of “criminality.” Instead, the focus should be in identifying the genesis of slums and the factors that force people to live –and in some cases survive- in such harsh conditions. The effects of the government’s disengagement which has been gradually reducing the provision of affordable and social housing, has been severely exacerbated by the privatization of public services and the financialization of land and housing. Who is to blame here for the proliferation of slums?

Habitat International Coalition (HIC) 1 and its global membership have been working for decades with impoverished communities in the global south that havebuilt not only their houses but entire neighbourhoods, with a vision that goes beyond the family core to create a sense of belonging and citizenship, as well as mechanisms against marginalization and social and urban segregation.

HIC understands these processes as “Social Production of Habitat” (SPH), the aggregate of all nonmarket processes carried out under inhabitants’ initiative, management and control to generate and/or improve adequate living spaces, housing and other elements of physical and social development, preferably without—and often despite—impediments posed by the State or other formal structure or authority 2.

SPH is a process in which people produce their own habitat: dwellings, villages, neighbourhoods, and even large parts of cities. They may be found in rural and urban settings, ranging from spontaneous individual/familial self-constructions, to collective productions that imply high levels of organization, broad participation, and agency for negotiation and advocacy with public and private institutions. In general SPH is implemented with very little or no official support and often despite a myriad of economic and institutional obstacles 3.

HIC believes that SPH processes should be accompanied of official support, guidance and plans for future improvements. Governments must provide the inhabitants with basic needs (sanitation, water, energy and security) and never refuse to provide them with these human rights.These obstacles come in the form of lack of regularization plans; no provision for future basic services; and cases in which water, electricity, and even land are monopolized by local mafias that increase the price of these basic rights. The issue of security (in particular of women and girls) and safety (floods, diseases, fires, pollution and food intoxications, among others) are a major threat since there is no planning support, nor contingency plans from the authorities of any kind.

With these concerns and questions, HIC has been focusing part of its work on how we understand SPH processes, its consequences and implications.Therefore, we can contribute to strengthen social justice, gender equality, and environmental sustainability, and work on the defence, promotion, and realization of human rights related to housing and land in both rural and urban areas. We present the results of a research carried out in a partnership with DPU (Development Planning Unit) of UCL (University College London). Developed by Blanca Larrain, this research analyses the experience of SPH processes in a sub-African context specifically in Mashimoni-Nairobi and reflects on its effects on new forms of substantive citizenship, as well as the possible use of SPH as a tool for promotion in an African context.

Alvaro Puertas

General Secretary

Habitat International Coalition (HIC)

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

For more info, please click here to download the document:

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

1 – The Habitat International Coalition (HIC) is the global network for rights related to habitat. Through solidarity, networking and support for social movements and organizations, HIC struggles for social justice, gender equality, and environmental sustainability, and works in the defence, promotion and realization of human rights related to housing and land in both rural and urban areas.

HIC is made up of more than 350 member organisations around the world and coordination offices in Mexico City, Cairo, New Delhi and Barcelona that work together to strengthen links between organisations and collectives, accompanying and supporting community processes and the most disadvantaged groups so that everybody has a safe place to live in peace and with dignity both in the countryside and in the city.

More information available at http://www.hic-gs.org/mission.php

2– HIC-HLRN’sHICtionary: Key Habitat Terms from A to Z. This reference work is the result of deliberation and debate across multiple specializations, regions and cultures within the membership of Habitat International Coalition (HIC).Available at http://www.hlrn.org/img/publications/HICtionary.pdf

3– Ortiz, E. y L. Zárate (2002)Vivitos y coleando. 40 años trabajando por el hábitat popular en América Latina[Alive and kicking.40 years working for people´s habitat in Latin America]. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana y HIC-AL, Mexico City.